Solana: Transactions, Messages & Address Lookup Tables

In the previous post, we broke down how Solana transactions are structured: messages, signatures, serialization, and how the runtime executes them.

In this final part, we’ll stop theorizing and start sending real transactions.

We’ll build a small on-chain program and a client that calls it. Then we’ll send the exact same instruction two different ways: first as a versioned (v0) transaction, and then as a v0 transaction using an Address Lookup Table.

We’ll look at the actual code that builds each transaction, inspect the messages that get signed, and see how accounts are passed, locked, and resolved at runtime.

Along the way, we’ll make several things explicit that most tutorials hide:

- why some accounts live in .accounts() and others in remainingAccounts

- how the same instruction can be executed under completely different messages

- what Address Lookup Tables really do (and what they don’t)

- what the IDL describes, and why it has nothing to do with execution

Nothing here relies on magic helpers. Every transaction is constructed deliberately, every account is passed explicitly, and every optimization is visible in the message.

By the end, you’ll know how to build v0 transactions with and without ALTs, when they behave the same, and why scaling on Solana is mostly a message-level problem.

This post closes the series by connecting instructions, messages, and tooling into one concrete, executable mental model.

From theory to execution

In the previous parts of this series, we treated Solana transactions almost like a protocol specification.

We broke them down into:

- instructions and their serialized data

- messages and account lists

- signatures, fees, and blockhashes

- and how the runtime executes a message once it’s accepted by the network

All of that can feel abstract when looked at in isolation. In real programs, those same concepts reappear not as definitions, but as constraints you have to work with.

This post is about seeing those ideas surface in practice.

How real programs experience instructions

From the program’s point of view, an instruction is still just:

- a byte array

- a list of accounts

- and a program ID

The program has no concept of:

- legacy vs versioned transactions

- address lookup tables

- fee payers or signatures

It only sees the result of the message: a fixed set of accounts it is allowed to read or write, in a fixed order.

That’s why well-designed programs:

- avoid hardcoding account layouts

- rely on passed-in accounts

- and stay agnostic to how the client constructs the message

In other words, programs live below the transaction abstraction.

How real clients experience messages

Clients live at the opposite end. They don’t care about program internals.

They care about:

- how many accounts must be passed

- how large the message becomes

- whether the transaction still fits on-chain

- and whether it can be signed and broadcast successfully

This is where concepts like:

- instruction batching

- versioned messages

- and Address Lookup Tables

stop being optional and start being architectural. The logic hasn’t changed. The instruction hasn’t changed. Only the message has.

What we’ll do next

With that context in mind, the rest of this post will walk through a small, intentionally boring program and show how:

- the same instruction executes under different messages

- nothing changes for the program

- and everything changes for the client

That’s where theory stops and real Solana development begins.

Solana Program

With the execution model in mind, we can now look at a concrete on-chain program. We won’t cover environment setup, deployment, or tooling configuration here those were already covered in earlier posts in the series. Nothing in this section depends on Anchor specifics beyond basic program structure.

Instead, we’ll focus entirely on the implementation and how it interacts with instructions and messages at runtime.

The program itself is intentionally simple.

It does not write state. It does not create accounts. It does not perform CPIs.

Its only job is to read token account data passed to it and return balances.

That simplicity is deliberate: it lets us isolate how accounts are passed, how instructions are executed, and how messages constrain execution, without unrelated complexity.

What this program shows

This program is intentionally simple. It doesn’t own state, create accounts, or perform CPIs. Its purpose is to read token balances in batches for a list of wallets and mints provided by the client.

Instead of querying balances one-by-one, the instruction accepts a vector of (wallet, mints) and processes them in a single execution. This makes it suitable for aggregators, dashboards, or off-chain systems that need to fetch many balances efficiently.

The instruction declares no required accounts. All token accounts are passed via ctx.remaining_accounts, which means the program only sees the accounts the message explicitly provides.

For each wallet and mint, the program derives the expected associated token account addresses for both SPL Token v1 and Token-2022, checks which one was included in the message, and reads the balance if it exists.

The result is returned using set_return_data, without writing anything on-chain.

The key takeaway is that this batching logic is completely agnostic to transaction format. Whether the client uses a legacy transaction, a v0 transaction, or a v0 transaction with an Address Lookup Table, the instruction behaves exactly the same. Only the message changes.

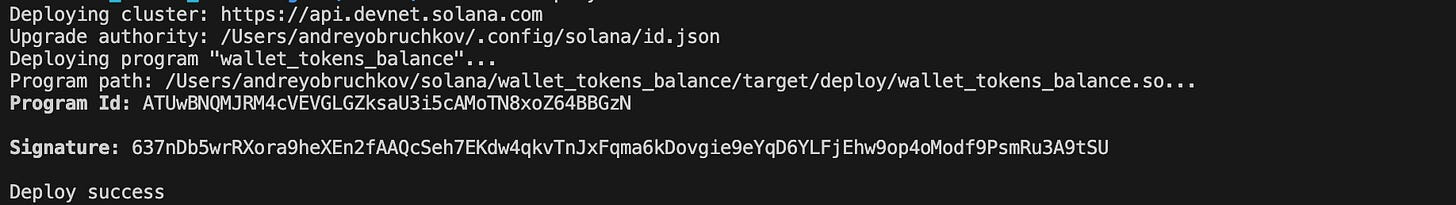

we will run:

anchor build

after the build is successfully finished, we can deploy it.

anchor deploy

After deploying, you can see the program on Solana Explorer (devnet) by its program-ID

you can see that on devnet.

Client side: Building the message the program will execute

The on-chain program is simple. The complexity lives on the client side, because Solana programs can only read accounts that the message explicitly provides.

So the client has two jobs:

- Figure out which token accounts (ATAs) might hold the balances

- Build a transaction message that includes those accounts and calls the instruction

In this example, we’ll also walk through creating an Address Lookup Table. As we’ve seen earlier, there’s a limit to how many account addresses can be included directly in a transaction message. In real-world scenarios, especially when batching or aggregating data, you quickly hit that limit. Address Lookup Tables are the mechanism Solana provides to scale beyond it.

Note on setup: For this example, I’m using two pre-created token mints and a pre-created Address Lookup Table. The details of how these tokens were created aren’t important for understanding this post. What matters is how their addresses are used inside the transaction message.

Step 1: Derive the Candidate Accounts (ATAs)

The input to the instruction is just a list of wallets and mints. But the program doesn’t receive token accounts from that. It receives accounts.

So the client derives the associated token account addresses for both token programs:

- classic SPL Token (v1)

- Token-2022

That’s why for every (wallet, mint) pair we compute two candidates using getAssociatedTokenAddressSync for both token program versions.

This mirrors the Rust helpers that derive ATAs on-chain. The client and the program must agree on these addresses.

Step 2: Only Pass Accounts That Actually Exist

Deriving ATAs is cheap, but many of them might not exist on-chain. Passing non-existent accounts would just waste space or fail during account loading.

So the client filters them using getMultipleAccountsInfo to check which candidate ATAs actually exist on-chain.

Only existing accounts are turned into remainingAccounts.

This is the crucial Solana rule in action: If it’s not in the instruction’s account list, the program can’t read it. So the client must bring the world with it.

Step 3: Remaining Accounts Are Message Wiring, Not “Program API”

When we build the instruction we call:

.accounts({})— empty because the program’s Anchor context is empty.remainingAccounts(remainingAccounts)— where the real work happens

The remainingAccounts becomes the instruction’s account metas list, which becomes part of the message, which becomes what the runtime loads and locks.

This is why this program scales with batching: the instruction data stays small while the message can carry lots of accounts.

Step 4: ALTs Optimize the Message, Not the Instruction

With batching, the message grows quickly because it has to include many account addresses. That’s where Address Lookup Tables come in.

We use a helper function ensureAltHasAddresses that:

- Fetches the ALT

- Checks which addresses are already stored there

- Extends the table with missing ones (only if needed)

Importantly: the ALT does not “send accounts to the program”.

It only lets the message reference account addresses more efficiently.

We still pass the token accounts via remainingAccounts. The ALT only changes how the message encodes those addresses.

Step 5: Send a V0 Transaction (Where ALT Actually Matters)

ALTs only work with versioned (v0) messages, so the client builds a v0 message explicitly using TransactionMessage and compiles it with compileToV0Message([altAccount]).

Then we sign and send a VersionedTransaction.

This is the key conceptual point: The instruction is identical. The program is identical. Only the message format changes.

v0 vs v0+ALT is purely a client-side message construction choice.

The transaction can be viewed in the Solana Explorer, showing the Program return data and the decoded balances.

Summary

In this post, we took Solana’s transaction model out of theory and into practice.

We built a real program, constructed real messages, and sent the same instruction using v0 transactions with and without Address Lookup Tables. Nothing changed for the program. Everything changed for the client.

That’s the core lesson: scaling on Solana is a message-level problem, not a program-level one. Programs execute instructions. Clients decide how those instructions are wrapped, encoded, and optimized.

In the next post, we’ll focus on the tokens used here, SPL Token vs Token-2022 and how their accounts differ, how ATAs are derived, and why those details matter when building real systems.

Learn more about Solana architecture from our articles

- Architecture & Parallel Transactions

- Account Model and Transactions

- Anchor Accounts: Seeds, Bumps, PDAs

- Instructions and Messages

- Transaction, Serialization, Signatures, Fees, and Runtime Execution

- SPL Token Program Architecture

Reliable Solana RPC infrastructure

Getting started with Solana on Chainstack is fast and straightforward. Developers can deploy a reliable Solana node within seconds through an intuitive Console — no complex setup or hardware management required.

Chainstack provides low-latency Solana RPC access and real-time gRPC data streaming via Yellowstone Geyser Plugin, ensuring seamless connectivity for building, testing, and scaling DeFi, analytics, and trading applications. With Solana low-latency endpoints powered by global infrastructure, you can achieve lightning-fast response times and consistent performance across regions.

Start for free, connect your app to a reliable Solana RPC endpoint, and experience how easy it is to build and scale on Solana with Chainstack – one of the best RPC providers.

Ethereum

Ethereum Solana

Solana Hyperliquid

Hyperliquid Base

Base BNB Smart Chain

BNB Smart Chain Monad

Monad Aptos

Aptos TRON

TRON Ronin

Ronin zkSync Era

zkSync Era Sonic

Sonic Polygon

Polygon Unichain

Unichain Gnosis Chain

Gnosis Chain Sui

Sui Avalanche Subnets

Avalanche Subnets Polygon CDK

Polygon CDK Starknet Appchains

Starknet Appchains zkSync Hyperchains

zkSync Hyperchains